Hokkaido’s History, Culture and Nature

Traditional Livelihood – Food / Clothing / Housing

Ainu culture has evolved with history. This section highlights the Ainu people’s traditional food, clothing and housing of 100 to 200 years ago.

Their current daily lives in terms of food, clothing and housing are almost the same as those of most people in Japan. However, in line with a growing recognition of Ainu’s traditional culture and a movement to restore various aspects of it in recent years, some Ainu people are proactively attempting to learn their traditional culture and pass it onto the next generation.

For instance, they increasingly wear their own traditional clothes at rituals and other formal occasions, which creates a growing demand for greater production of their traditional clothes. In terms of the traditional diet, some Ainu people use traditional ingredients to prepare new cooking-style dishes, and some use non-traditional seasonings.

As for housing, consideration has been given to housing design so that units specifically designed for meetings and ceremonies often contain a hearth and other features involved in rituals.

Outline of Ainu clothing

There are different kinds of Ainu clothing depending on the material, design patterns and regional characteristics. Clothing is also divided based on the age and gender of the intended wearer and the occasion. Some clothes are worn during daily life and work, while others are intended to be worn at rituals.

Clothes made of animal hides and furs

Hide and fur clothes

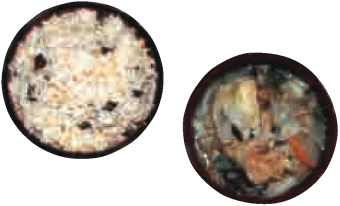

Various hides and furs both of land animals like bears, deer and foxes as well as sea mammals like seals, sea otters and fur seals are used to make clothes.

(Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum, Biratori Town collection)

Fish skin clothes

Pieces of salmon, trout and other fish skin are patched together to create clothes with tighter sleeves and a wider hem than other clothes, and is similar to a western style one-piece dress.

(Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum collection)

Clothes made of plant fibers

Bark clothes

Fibers from the inner bark of one kind of elm and Japanese linden trees are woven into textile fabrics for dress-making, which are called attush. The elm is said to be the best suited for dress-making among the various materials because it has very soft fibers.

(Ainu Museum collection)

Grass clothes

Nettle tree fibers are woven into textile fabrics. These fibers are thinner and whiter than those of the elm tree.

(Botanic Garden, Field Science Center for Northern Biosphere, Hokkaido University)

Clothes made of cotton

Old cotton clothing and remnants of precious clothing obtained through early trade practices were used to make these clothes that were found in many areas and called by different names in the Ainu language.

(Ainu Museum collection)

Foreign clothes

Garments imported from other regions were considered very valuable and the Ainu wore them as formal clothes over their native clothes like attush.

Clothes from Northeast China

These clothes are called “Santan-fuku” or “Ezo Nishiki” in Japanese. Garments for the Court Officials of the Ching (Ch’ing) Dynasty were brought to Hokkaido from what is known today as Northeast China and Primorskii Krai through a trade route with Sakhalin.

(Ainu Museum collection)

Clothes from Honshu

Ceremonial overgarments, wadded silk garments, garments for Noh-drama performance: beautifully embroidered silk garments that the Ainu wore as such or after removing the inner parts

Battle surcoat: a coat worn over armor by a warlord

Others

Underwear / Routine Clothing

Previous routine clothing, made of animal hides, tree bark, grass or cotton, characteristically has much less decorative patterns than the ceremonial clothes and garments.

At home, women wore clothes called mour in many areas and would put on more decorative and precious clothing as mentioned above over their routine clothing when they had guests or went out to public places.

Reportedly, Ainu men wore underwear or loincloths made of tree bark or cotton.

(Ainu Museum collection)

Pattern making

The patterns on the clothes, which are characteristic of the region of origin, are made by patchwork and embroidery.

Embroidered patterns apparently serve as a charm against evil spirits, which was believed or not, depending on the people and the region. Some seniors who know the past well believe that thorny patterns have a special meaning, but others say they don’t.

Food that the Ainu people relied on

There were various consumption patterns concerning the foodstuff that the Ainu relied on, depending on the region where they lived. For example, people living near a coastal environment had more opportunities to eat seafood, while those living inland depended more on mountain products. This section highlights food the Ainu people ate and how they obtained it.

1 Hunting

The animals hunted by the Ainu were Hokkaido sika deer , brown bears, raccoons, squirrels and rabbits and their meat was mostly cooked in a soup or roasted. Meat stored after drying was boiled again in a soup. Wild birds including copper pheasant, jay sparrow, sparrow and ducks were cooked in a soup or roasted.

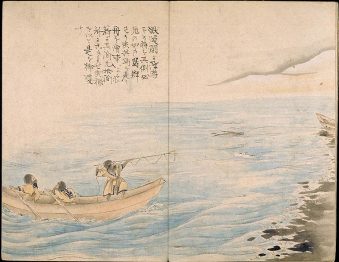

2 Fishing

The species of fish caught in the rivers and lakes include salmon, trout, dolly verden, white spotted charr, Japanese huchen, charr, rainbow smelt, pond smelt, capelin, dace, crucian carp, loach, sturgeon, and river shrimp. Fresh fish were cooked with edible wild plants in a soup or were spit-roasted.

Salmon was sometimes eaten in the form of Ruybe (ru-ipe), a frozen raw fillet. Salmon roe was consumed with gruel or soup and dried as a way of preservation.

Ruybe(ru-ipe)

Today, Ruybe is a popular dish of frozen raw salmon fillet .Ruybe is a combination of two words; “ru” which means melting and “ipe” a food stuff. Reportedly, the Ainu consumed frozen salmon after the entire salmon had hung under the eaves during winter.

(Northern Studies Collection, Hokkaido University Library)

The regions along the coasts of Hokkaido and Sakhalin had a tradition of active sea fishing and hunting for cod, flounder, anchovy, herring, swordfish, sunfish, whale, seals and fur seals. Their meat, oil and internal organs were consumed, while the hides of sea mammals were used for clothing.

3 Gathering

Edible wild plants were gathered from spring to fall and the various parts of the plants like their buds, stems, leaves, bulbs, roots and berries were consumed depending on the type of plant.

From spring to summer, various wild plants such as alpine leek, anemone, wild rocambole, rectifolia, Heracleumlanatum, Eastern skunk cabbage, butterbur sprout, ostrich fern (sprout), bracken, royal fern, felon herb, Japanese butterbur, Angelica edulis were gathered for consumption. The roots and bulbs of Adenophoratriphylla, Codonopsislanceolata, Dogtooth violet, Smilacina, Chocolate Lily, Cardiocrinumcordatum, etc. were consumed.

From summer to fall, berries like sweet brier, hardy kiwi, and mulberry; and acorns and seeds from walnut trees, Japanese chestnut trees, Amur Corktrees, water oaks, and oaks; and fruit like blue honeysuckle (haskap), wild grapes and wild strawberries, as well as underground berries from Chinese hog-peanut; and roots from rough potatoes and Arisaemapeninsulae were gathered.

Rataskep

The dish called Rataskep has often been introduced as one of the typical Ainu dishes. It is made of either edible wild plants, commonly found vegetables or beans, or a mixture of some of these different ingredients. For seasoning, oil and salt was used.

(Photo courtesy: Shinhidaka Ainu Museum)

4 Agriculture

Barnyard millet and foxtail millet were cultivated from early times as proved by evidence that the Ainu language was used for these grains, and that millet was discovered at archeological sites. According to the records kept during the middle of Japan’s Edo era, the Ainu cultivated potatoes, grains including proso millet, wheat, buckwheat and corn, beans such as soybeans, adzuki beans and cowpea and vegetables including turnip called Atane and Japanese radish.

Grains were consumed in the form of gruel on a daily basis, and were steamed for festivals and rituals. Grains were also used to make dumplings or as ingredients of home brewed liquor.

Daily meals

Most daily meals usually consisted of soup and gruel.

The types of a soup included soup with edible wild plants, meat, fish and seaweeds. The soup, which usually contained a lot of ingredients, was cooked with salt and oil for seasoning.

To make gruel, grains such as barnyard millet, proso millet, foxtail millet, rice and corn were cooked in a large amount of water. Dried alpine leek, starch of Cardiocrinumcordatum, dried salmon roe, potatoes, beans and pumpkins were sometimes added to the gruel.

(Photo courtesy: Shinhidaka Ainu Museum)

Special meals for festivities and rituals

Steamed grains, Rataskep, dumplings and home-brewed liquor were commonly prepared for festivities and such rituals as bear spirit sending, prayers to gods and house warming.

(Photo courtesy: Shinhidaka Ainu Museum)

Food Processing for Preservation

The food that Ainu obtained through hunting, fishing, gathering and farming were not only consumed immediately, but were also stored as reserve food for the long winter period and in preparation of possible future food shortages. Edible wild plants were processed for preservation especially from spring through summer, and besides the wild plants, cultivated crops as well as fish were also processed for preservation in fall.

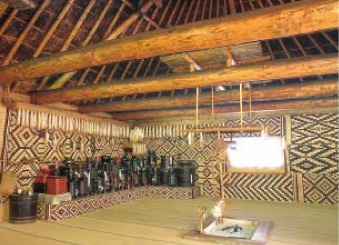

Outline of Dwelling Systems

(The Ainu Museun)

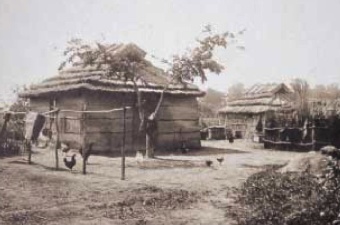

The design of the Ainu housing systems differs depending on the region of the residence and the individual household. A unit with a single large rectangular room and a hearth in the middle appears quite common. It often has a small building outside the doorway that was used as an entrance and for storage. The materials used for the posts, roof, walls and floor included trunks, branches and various kinds of bark and grass. The huge amounts of materials necessary to thatch the walls and roofs were usually procured from locally available resources.

In Ainu language, “Cise” means “House”, which is pronounced by placing a high pitch on “se” instead of “ci”. This word has often been used, even in the Japanese vernacular, specifically to refer to a house thatched with saw grass or bamboo grass.

However, the word “Cise” still exists in the Ainu language, and is used even to refer to housing units built by modern construction methods. Ainu seniors often use the word as such in their conversation. Despite the changes in the selection of materials and construction methods, “Cise” remains unchanged and still means a house in the Ainu language.

Room Arrangement and Interior Finishing

(The Ainu Museun)

The room had windows, and it was believed that the gods entered and left through one of the windows. The window is set to face in a sacred direction based on well-known teachings.The space between this sacred window and the hearth in the middle of a room is considered as sacred space inside the room, and guests are sometimes invited to sit there.

The floor is covered with layers of grass, reed screens and matting. A low platform is sometimes placed by the wall as a bed.

In one method of making a hearth, a hole is dug and then layers of leaves, gravel and volcanic ash are placed in this order.

The walls inside the room are occasionally finished with matting while the window or the doorway is sometimes finished with hanging reed screens or matting.

Surroundings of the main unit

(The Ainu Museun)

An altar, a bear cage and a storage area are, in some cases, located around the main unit. The altar is placed outside facing the sacred window through which the gods supposedly enter and leave.

In the proximity of the house, the waste disposal area was designated by some households, and rice bran and ash from the hearth were sometimes separated from the rest of the waste. Some dwellers used racks and rods for the drying of fish and meat and used rods for laundry. Others put a wind and snow fence made with saw grass around the house.

Facilities and organizations in which visitors can learn about the traditional food, clothing and housing of the Ainu people

■Located in Hokkaido

Asahikawa City Museum (in Taisetsu Chrystal Hall)

Branch of Asahikawa City Museum –Ainu Bunka no Mori Densho no Kotan

- Address9-sen Nishi 4-go, AzaChikabumi, Takasu, Kamikawa-gun

- Tel0166-52-1541

- LinkBranch of Asahikawa City Museum -Ainu Bunka no Mori Densho no Kotan (In Japanese)

Kawamura Kaneto Ainu Museum

- LinkKawamura Kaneto Ainu Museum (In Japanese)

Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum

- LinkNibutani Ainu Culture Museum (In Japanese)

Kayano Shigeru Nibutani Ainu Museum

- LinkKayano Shigeru Nibutani Ainu Museum (In Japanese)

Yukar no Sato (in Noboribetsu Bear Park: from May to October)

- Address224 NoboribetsuOnsen-cho, Noboribetsu

- Tel0143-84-2225

- LinkYukar no Sato (in Noboribetsu Bear Park: from May to October) (In Japanese)

National Ainu Museum

Hokkaido Museum

- LinkHokkaido Museum

* For further information, please visit the following website of Hokkaido Museum which provides details through a handbook on Ainu culture –pon kanpi-sos.